[social facebook_url=”http://www.propstore.com/cms/nostromo-a-legend-born-and-born-again-part-2-2/”]

When last we left the Nostromo, it was an ailing derelict, lost to the punishment of time and the elements. All hope seemed lost… But then, a beacon appeared on the horizon.

Enter: Stephen Lane and his rescue ship Propstore.

In 1998, the England native Lane turned his hobby—collecting original movie props and costumes—into a full-time business. But his vision was not that of a stock retail operation—buying props, marking them up, and selling them to collectors. Instead, Lane saw himself and his cohorts as “movie archaeologists,” scouring the world for the hidden treasure troves of props and costumes that were just waiting to be found. Sure it was his business. But Stephen was a collector first and foremost. His work drew from a well of immense passion and was pursued with a largely conservationist bent. Countless important film artifacts have been lost to time and to the rubbish bin over the decades and Lane and his growing army of collectors sought to put an end to these travesties, one prop at a time. Propstore grew into a behemoth over the next decade-plus, amassing over 15,000 square feet of warehouse and office space in two major cities on two different continents: London and Los Angeles.

This made the Nostromo an ideal candidate to be awoken from its hypersleep in KNB’s storage facility.

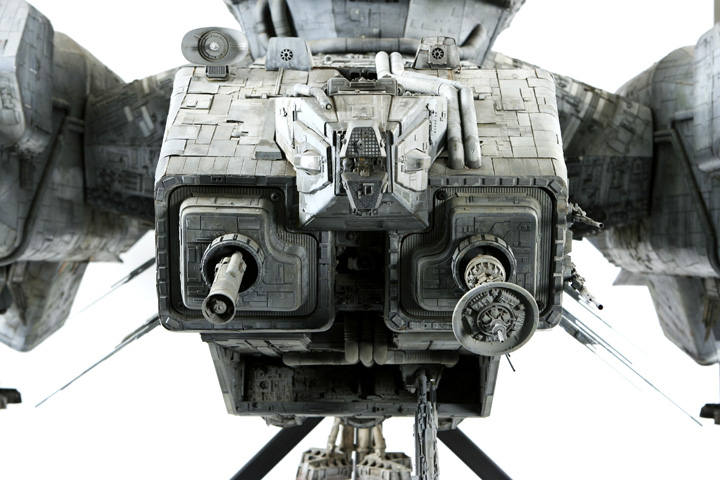

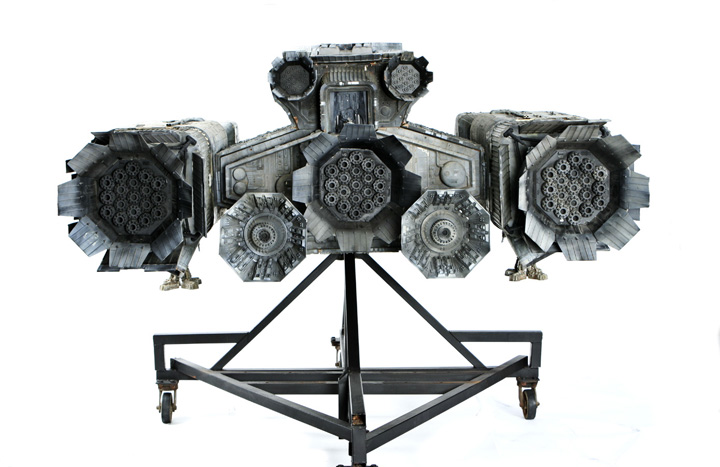

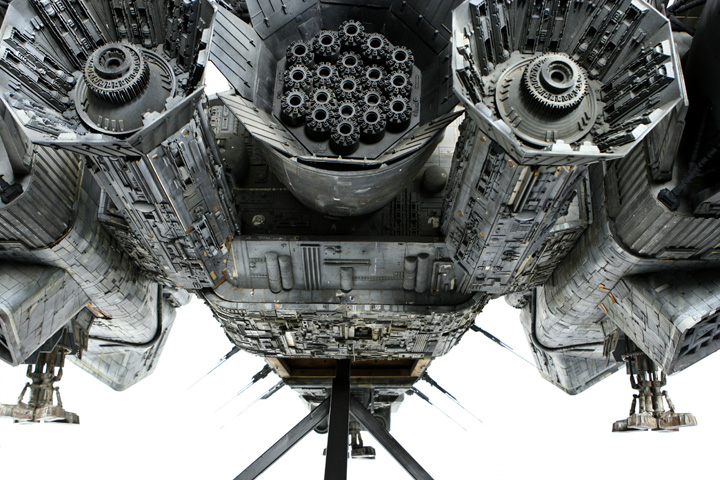

In 2007, Lane and head of Los Angeles operations Brandon Alinger worked out a deal with KNB that would see the Nostromo finally resurrected and put on display where film fans could enjoy it again. The model was freighted into Propstore’s Los Angeles office where the Nostromo’s condition was fully assessed. The seams—both of the styrene detail work and the wooden understructure—were pulling apart. The wood had splintered, cracked, eroded, and shrunk. Years of rain had soaked into the wood and dried it out, the same conditions that can lead to dry rot. The Nostromo was not in good shape. The miniature was in desperate need of restoration, but the work was beyond Propstore’s internal resources. Bring back life form. Priority One. All other priorities rescinded.

Okay, fine. But who the hell do you call when you need to restore a circa 2087 Commercial Space Tug? The ideal scenario for the restoration would have been to reunite the model with its parents, Brian Johnson and his ALIEN visual effects team. Unfortunately, the Nostromo’s bulk and general condition precluded the possibility of it being sent back to the United Kingdom.

So Propstore met with a number of effects houses in Los Angeles before deciding on the legendary Grant McCune Design, the guys who practically invented sci-fi movie model making.

Pulling into their parking lot deep in the baking heat of Los Angeles county’s San Fernando Valley, the Grant McCune Design facility doesn’t look like much. Except the parking lot itself is a landmark in movie history. In 1977, Grant McCune Design’s—then the very first incarnation of Industrial Light and Magic (ILM)—parking lot was the site of the filming of the famous Death Star trench from George Lucas’s original STAR WARS. The eighty foot long trench was too expansive to house inside ILM’s facility, so they built it outside. In the parking lot.

Grant McCune and his team, including Don Trumble, Bill Short, and visual effects legend John Dykstra himself, designed and built the models that made STAR WARS well… STAR WARS. But when the team was approached with the opportunity to create the practical visual effects for STAR WARS, they had never even built a model before! They were already accomplished tinkerers and innovative builders, so the prospect wasn’t terrifying: it was a challenge.

It was through the resulting process that many techniques that are now common practice in model-making were invented, including using fiber optics to create internal lighting and George Lucas’s “used universe” concept, which meant making the model look old and lived-in, despite the fact that it had been built in just a few weeks. A crucial part of this visual effect was “kit-bashing,” and the original STAR WARS saga remains the finest example of kit-bashing in practice. After George Lucas purchased ILM and moved it to Northern California, John Dykstra and Grant McCune opened their own effects shop. Apogee would go on to explode in the 1980s heyday of practical visual effects (before the shift to computer generated effects). Before it restructured again in the early 1990s and became Grant McCune Design, Apogee was the biggest model-maker working in the movie business.

With Grant McCune Design’s unmatched pedigree, Propstore saw his shop as the perfect rehabilitation facility for the ailing Nostromo.

Thankfully, Grant McCune Design modeler maestros Monty Shook and Jack Edjourian agreed to tackle the restoration. Both designers had worked on a number of popular films, but the chance to restore an icon like the Nostromo thrilled them. When they first saw the Nostromo in Propstore’s storage facility, Shook and Edjourian were amazed at its sheer size. But they were also amazed at the overwhelming amount of work that lay in front of them.

In fact, an initial inspection of the wooden musculature had them concerned that the degradation was too far gone for a true restoration versus a scratch rebuild. They worried about dry rot and even termites having afflicted the wood, but fortunately, a more detailed inspection revealed that the model’s robust initial construction and a little bit of luck had preserved the Nostromo from a terminal diagnosis. Even now, Edjourian and Shook still marvel at the Nostromo’s steel support frame, as they had never seen anything that heavy-duty. Still, Grant McCune Design was amazed that the model lasted as long as it did. The wood had worn so thin that it was a wonder that it was still in tact. To bridge the different sections of the ship, the original design team used a thin ply that might have been weather-sealed, but no evidence of this remained. It seemed like the Nostromo had just barely held on, knowing this succor would come.

It was very important to both Propstore and to Grant McCune Design to keep the Nostromo as true as possible to its original makeup. This meant fixing broken and worn parts rather than replacing them, even when the fix was more time-consuming than a casting or a replacement. This was going to be an archival-quality restoration, and one handled with the utmost of expertise and care.

Agreements were made and Grant McCune Design set to work.

The first step was a thorough cleaning of the model’s hollow interior, an unenviable task that fell on Edjourian’s shoulders. And he couldn’t believe what he found. He was pulling out seemingly endless fistfuls of rotting leaves and other awful-smelling organic filth. How did all this crap find its way inside the narrow nooks and crannies of a model spaceship? Well, much like the movie ALIEN’s Nostromo—and much to Edjourian’s horror—Propstore’s Nostromo also had a stowaway.

Something has attached itself to him. We have to get him to the infirmary right away.

What kind of thing? I need a clear definition.

An organism. Open the hatch.

Thankfully, this Nostromo’s dark passenger was not an acid-bleeding xenomorph whose structural perfection was only matched by its hostility. Nor was it Captain Dallas’ mother-in-law.It was an opossum. A very dead one who had left behind only her skeletal remains as evidence of her one-way visit to the Nostromo. Not wishing to find other such surprises or tear out the nest of (no longer functional) fiber optics that also lurked within, Edjourian began photographing the interior of the model as he dug deeper inside. To his surprise, the opossum didn’t die alone. Inside, he found a second, complete opossum skeleton, possibly that of a mate or an adult offspring. But to sci-fi and horror guys, this revelation wasn’t horrifying. It was kitschy. In fact, at the time of this writing, the opossums were being lovingly reassembled at Grant McCune Design as a piece of macabre model-making memorabilia.

In addition to California wildlife, Edjourian also found an entire CO2 gas system inside the Nostromo. This was used during the landing sequence to create the dramatic exhaust vapors that Ridley Scott so loved to employ in order to create a “film noir” atmosphere in his sci-fi films.

Once it had been thoroughly cleaned out, a proper restoration could begin. They reclamped and reglued the suffering wood understructure in an effort to get the model both symmetrically and structurally sound again. As they snapped a photographic record of the Nostromo’s original state for reference, they peeled off the plastic parts to get to the softened wood beneath. This process is what led them to the surprising discovery that chloroform was used as the original bonding agent, something that certainly would not be done today. The repairs also yielded physical evidence of the Nostromo’s aborted yellow paint scheme, as there were still traces of the nautical yellow in the cracks and crevices of the now flat-gray ship.

The shoring up of the Nostromo’s structural integrity alone took weeks worth of man-hours, but was the most important part of the restoration as it was the work that would hopefully ensure the Nostromo decades of longevity to come. Once the model was structurally sound again, it was time for the detail work.

That’s where the real fun began for the self-professed “model geeks” at Grant McCune Design. “It was the world’s greatest jigsaw puzzle,” Jack Edjourian recalls. The restoration team was looking at tables and table’s worth of tiny styrene pieces, most of them just a few square inches in size. But they had a virtual reference library of photographs of the original Nostromo thanks to Propstore’s unparalleled research efforts. Also, a fortunate happenstance of the way the Nostromo was weathered by the elements was that the years of dirt and rain left little outlines on the wooden understructure where it had run into the seams between the styrene detail pieces. Mother nature had left behind a template for what the original model looked like! So all Grant McCune Design had to do was figure out what went where. Still no small task, but with the pieces that they rescued and with a supplemental bag of parts that Bob Burns had preserved indoors, the Nostromo was actually starting to look like herself again. Once these pieces had been cataloged and fitted, it was clear what was missing and where it was missing from.

Recall that the Nostromo was originally constructed using the parts from a few off-the-shelf model kits. Back to our old friend “kit-bashing.” Well the reason we know this is not necessarily due to a thirty-year old memory of a British visual effects team member, but because of Grant McCune Design’s own Jack Edjourian. Using his encyclopedic modeler’s mind, he went about identifying the parts used by the original “widgeteers.” In his investigation, Edjourian was surprised to discover that virtually no gang-molding had been done by Brian Johnson’s effects team. That means that instead of picking a part that they liked and casting it in silicon to make as many copies as they needed, the design team used original parts from the model kits they liked. Again and again and again. This tedious, iterative process amazed everyone at Grant McCune Design. But Johnson sheds light on the mystery, “One reason we didn’t do any gang molding was because in the UK at that time the products were somewhat unstable… I saw results that had not lasted many weeks in front of hot lamps and we had to shoot at high speed because of the dust effects…”

The Nostromo was a “labor of love” back in 1978, too.

So a-kit-bashing Edjourian and his team went. He identified the parts he needed and the models from which they originated and went to his model supplier and started buying up the old kits again. In the model kit business, not much changes over time. If the model is still being produced, the original dies are used over and over so the parts Edjourian would be finding (if available) would be identical to the ones used three decades earlier. There was a bit of trepidation at the end of this process as Edjourian was looking for a particular British Matilda tank model that was still around but a bit rare. As fate has it, Grant McCune Design’s model supplier happened to have just one of these left in stock.Fortune suddenly seemed to be following the Nostromo’s restoration just as misfortune had shadowed her for her prior twenty-seven years.

Though the original effects team hadn’t employed gang-molding, Grant McCune Design wasn’t about to hunt down of model kits just for the sake of one-upsmanship. Whenever possible, original parts from the Nostromo were used for the mold master. Then, the parts needed in multiples were thrown into two-part silicon molds and Grant McCune Design could make exact duplicates of all the parts they needed in durable urethane plastic. Over thirty molds were created in order to fabricate parts that were completely accurate to the original. All viable parts could then be heated and shaped onto their place on the model’s surface.

One piece at a time, Grant McCune Design trudged forward. Molding, pulling, heating, shaping, gluing.

During this time-consuming process, freelance modelers would come into Grant McCune Design to do visual effects work on a film, see the Nostromo being restored, and cleverly worm their way into the restoration process. To a visual effects artist, the Nostromo is like an original Shelby Cobra to a motor-head: if you see one being restored, you want to get yourself under that hood. Thus, in a shop full of model geeks, the Nostromo never found itself in want for labor.

Until his passing in late 2010, Grant McCune himself participated in a solely supervisory role at his shop, and still spent a good amount of time at the facility during the restoration in 2007. Upon seeing his team restoring the Nostromo, he was said to have remarked: “We didn’t win an Academy Award because of that.” At the 1979 Academy Awards, Apogee lost their Oscar® bid for their work on STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE to Brian Johnson’s ALIEN visual effects team. But Shook had a salve for McCune’s old wound, “Well the good part is, we’re getting to fix it.”

The structure was sound and the kits were bashed. It was time to paint the Nostromo. But Grant McCune Design couldn’t have an old, beat-up space tug roll out of their shop looking like it had just come out of Weyland-Yutani’s factory. They had to weather it. After studying their extensive photographic reference and evidence they could collect from the cleaner pieces that had been spared from outdoor storage, Shook and Edjourian had a pretty good picture of what the Nostromo looked like when it was wheeled onto the soundstage at Bray Studios back in 1978. The intent was not to alter the original paint wherever possible, instead focusing only on the restored sections of the ship while using the sections with the original paint as a guide. The real trick was to create a seamless effect for the Nostromo that made it appear as though it had been painted and weathered in one application with a single set of materials, even though the model had really been painted by two different effects teams, thirty years apart from one another.

To achieve this look, Grant McCune Design painted the ship in sections, hitting one at a time. They applied six different tones of gray in a patchwork, favoring the paintbrush over the airbrush for a less “deliberate” look. Then, to make the ship appear weathered, they went over the refurbished sections with a chalky wash before finishing it with a wet, dark wash that was meant to “age” the new paint. This was all done while ensuring that the value and texture of the restored sections matched the adjacent sections with the original paint job.The entire restoration took the better part of a year in between deadline-driven film and TV jobs, with Shook, Edjourian and four other artisans spending the equivalent of three months of 40 to 50 hour workweeks on the Nostromo. About twenty percent of the restoration—over 400 man-hours—was spent on the structural repairs alone. But the bulk of the work, some sixty percent of it, Shook guesses, was spent “widgeteering,”—figuring out what parts went where, what was missing, what model kits the pieces could be farmed from, gang-molding and then shaping and application. The remaining labor was the paint job and final assembly.

This time, there would be no self-destruct sequence for Ripley’s Nostromo. After being on the very precipice of a one-way trip to a sci-fi junkyard somewhere outside Los Angeles, she was alive and kicking one again.

It’s an interesting combination of elements making him a… tough little son-of-a-*****.The final product is visually stunning on its own. Compare it to photos of the model’s condition prior to the restoration and its current state is a minor miracle. The Nostromo’s new owner Stephen Lane was equally taken with it.

"I’m so proud to have now become part of the history of this incredible model. She is a sight to behold and I encourage anybody who is visiting Los Angeles to come and see this phenomenal piece of work in person.”

In the end, the Nostromo’s restoration goes far beyond being some hobbyist’s passion project. It’s the work of a film historian attempting to preserve a crucial artifact from one of the medium’s genre landmarks. Without Bob Burns’s initial move to save the Nostromo from the rubbish pile at Bray Studios, KNB Effects’ rescue and, most importantly, without Propstore’s final intervention, the fans and the annals of movie history would have only memories to cherish.

Instead, thanks to the dedicated and forward-looking few, we have the Nostromo. In her full, former, industrial glory.

Final report of the commercial starship Nostromo, third officer reporting…

The other members of the crew, Kane, Lambert, Parker, Brett, Ash and Captain Dallas, are dead. Cargo and ship destroyed. I should reach the frontier in about six weeks. With a little luck, the network will pick me up.

This is Ripley, last survivor of the Nostromo, signing off.

Thanks to guys like Bob Burns, Greg Nicotero, Howard Berger and Stephen Lane, this Nostromo dodged the climatic self-destruct sequence. And now, it can be enjoyed by ALIEN and sci-fi fans old and new for generations to come.

This article is dedicated to the memory of the late, great Grant McCune, who kit-bashed many of our childhoods, making us the geeks we are today.

Thank you, Grant. You will be sorely missed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

ALIEN Visual Effects Team:

Nick Allder, Martin Bower, Simon Deering, Brian Eke, Martin Gant, John Hatt, Ron Hone, Guy Hudson, Brian Johnson, Andrew Kelly, Phil Knowles, Dennis Lowe, Roger Nichols, John Pakennham, Bill Pearson, Phil Rae, Jon Sorenson, and Neil Swan.

Grant McCune Design Nostromo Restoration Team:

Monty Shook, Jack Edjourian, Scott Burton, John Eaves, Olivia Miseroy, Jason Kaufman, Eric Tucker, and David Venegas.

Also, special thanks to:

Bob Burns and Greg Nicotero and Howard Berger of KNB EFX Group.